Psychology

New World Library

2008

418

I don't know why it took me so long to read this book. It is excellent. All the myths, all the legends, all the....stories follow a basic formula. Campbell shares the format and shows the connections between them all. Buddha, Jesus, Odinson....all the same format. All the same "Hero's Journey".

The Hero With a Thousand Faces

Joseph Campbell

1 Myth and Dream

It would not be too much to say that myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation

In the field of folk psychology, has been seeking to establish the psychological bases of language, myth, religion, art development, and moral codes.

The bold and truly epoch-making writings of the psychoanalysts are indispensable to the student of mythology; for, whatever may be thought of the detailed and sometimes contradictory interpretations of specific cases and problems, Freud, Jung, and their followers have demonstrated irrefutably that the logic, the heroes, and the deeds of myth survive into modern times

That of the tragicomic triangle of the nursery—the son against the father for the love of the mother. Apparently the most permanent of the dispositions of the human psyche are those that derive from the fact that, of all animals, we remain the longest at the mother breast. Human beings are born too soon; they are unfinished, unready as yet to meet the world. Consequently their whole defense from a universe of dangers is the mother, under whose protection the intra-uterine period is prolon

The unfortunate father is the first radical intrusion of another order of reality into the beatitude of this earthly restatement of the excellence of the situation within the womb; he, therefore, is experienced primarily as an enemy

The doctor is the modern master of the mythological realm, the knower of all the secret ways and words of potency. His role is precisely that of the Wise Old Man of the myths and fairy tales whose words assist the hero through the trials and terrors of the weird adventure.

The so-called rites of passage, which occupy such a prominent place in the life of a primitive society (ceremonials of birth, naming, puberty, marriage, burial, etc.), are distinguished by formal, and usually very severe, exercises of severance, whereby the mind is radically cut away from the attitudes, attachments, and life patterns of the stage being left behin

It has always been the prime function of mythology and rite to supply the symbols that carry the human spirit forward, in counteraction to those other constant human fantasies that tend to tie it back.

The psychoanalyst has to come along, at last, to assert again the tried wisdom of the older, forwardlooking teachings of the masked medicine dancers and the witch-doctor-circumcisers; whereupon we find, as in the dream of the serpent bite, that the ageless initiation symbolism is produced spontaneously by the patient himself at the moment of the release

The figure of the tyrant-monster is known to the mythologies, folk traditions, legends, and even nightmares, of the world; and his characteristics are everywhere essentially the same. He is the hoarder of the general benefit. He is the monster avid for the greedy rights of “my and mine.” The havoc wrought by him is described in mythology and fairy tale as being universal throughout his domain.

The inflated ego of the tyrant is a curse to himself and his world—no matter how his affairs may seem to prosper.

The hero is the man of self-achieved submission.

As Professor Arnold J. Toynbee indicates in his six-volume study of the laws of the rise and disintegration of civilizations,17 schism in the soul, schism in the body social, will not be resolved by any scheme of return to the good old days (archaism), or by programs guaranteed to render an ideal projected future (futurism), or even by the most realistic, hardheaded work to weld together again the deteriorating elements. Only birth can conquer death—the birth, not of the old thing again, but of something new. Within the soul, within the body social, there must be—if we are to experience long survival—a continuous “recurrence of birth” (palingenesia) to nullify the unremitting recurrences of death there is nothing we can do, except be crucified—and resurrected; dismembered totally, and then reborn.

Theseus, the hero-slayer of the Minotaur, entered Crete from without, as the symbol and arm of the rising civilization of the Greeks. That was the new and living thing.

Note 16: T.S. Eliot The Waste Land

Note 17: Arnold Toynbee, A Study of History

Dream is the personalized myth, myth the depersonalized dream; both myth and dream are symbolic in the same general way of the dynamics of the psyche

The hero, therefore, is the man or woman who has been able to battle past his personal and local historical limitations to the generally valid, normally human forms.

His second solemn task and deed therefore (as Toynbee declares and as all the mythologies of mankind indicate) is to return then to us, transfigured, and teach the lesson he has learned of life renewed.

Note 20: It must be noted against Professor Toynbee, however, that he seriously misrepresents the mythological scene when he advertisises Christianity as the only religion teaching this second task. ALL religions teach it, as do ALL mythologies and folk traditions EVERYWHERE. Toynbee arrives at his misconstruction by way of a trite and incorrect interpretation of the Oriental ideas of Nirvana, Buddha and Bodhisattval then contrasting these ideals, as he misinterprets them, with a very sophisticated rereading of the Christian idea of the City of God.

Perhaps some of us have to go through dark and devious ways before we can find the river of peace or the highroad to the soul’s destination.”

Dante’s “dark wood, midway in the journey of our life,” and the sorrows of the pits of hell: Through me is the way into the woeful city, Through me is the way into eternal woe, Through me is the way among the Lost People

…variety of Pandora’s box—that divine gift of the gods to beautiful woman, filled with the seeds of all the troubles and blessings of existence, but also provided with the sustaining virtue, hope.

Alas, where is the guide, that fond virgin, Ariadne, to supply the simple clue that will give us courage to face the Minotaur, and the means then to find our way to freedom when the monster has been met and slain?

2. Tragedy and Comedy

Modern romance, like Greek tragedy, celebrates the mystery of dismemberment, which is life in time. The happy ending is justly scorned as a misrepresentation; for the world, as we know it, as we have seen it, yields but one ending: death, disintegration, dismemberment, and the crucifixion of our heart with the passing of the forms that we have loved.

Poetics of Aristotle, tragic katharsis (i.e., the “purification” or “purgation” of the emotions of the spectator of tragedy through his experience of pity and terror) corresponds to an earlier ritual katharsis (“a purification of the community from the taints and poisons of the past year, the old contagion of sin and death”), which was the function of the festival and mystery play of the dismembered bull-god, Dionysos

…the fairy tale of happiness ever after cannot be taken seriously; it belongs to the never-never land of childhood, which is protected from the realities that will become terribly known soon enough

The happy ending of the fairy tale, the myth, and the divine comedy of the soul, is to be read, not as a contradiction, but as a transcendence of the universal tragedy of man.

Tragedy is the shattering of the forms and of our attachment to the forms; comedy, the wild and careless, inexhaustible joy of life invincible. Thus the two are the terms of a single mythological theme and experience which includes them both and which they bound: the down-going and the up-coming (kathodos and anodos), which together constitute the totality of the revelation that is life, and which the individual must know and love if he is to be purged (katharsis=purgatorio) of the contagion of sin (disobedience to the divine will) and death (identification with the mortal form).

It is the business of mythology proper, and of the fairy tale, to reveal the specific dangers and techniques of the dark interior way from tragedy to comedy. Hence the incidents are fantastic and “unreal”: they represent psychological, not physical, triumphs.

…the point is that, before such-and-such could be done on earth, this other, more important, primary thing had to be brought to pass within the labyrinth that we all know and visit in our dreams.

3 The Hero and the God

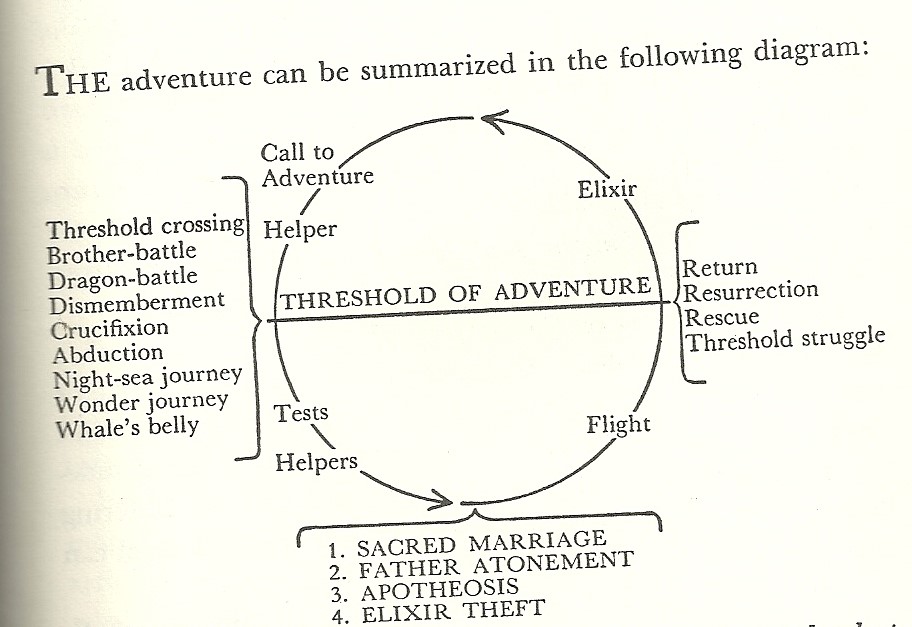

THE standard path of the mythological adventure of the hero is a magnification of the formula represented in the rites of passage: separation—initiation—return: which might be named the nuclear unit of the monomyth. A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

A majestic representation of the difficulties of the hero-task, and of its sublime import when it is profoundly conceived and solemnly undertaken, is presented in the traditional legend of the Great Struggle of the Buddha

The Old Testament records a comparable deed in its legend of Moses,

The Lord gave to him the Tables of the Law and commanded Moses to return with these to Israel, the people of the Lord.

Note 37: This is the most important single moment in Oriental mythology, a counterpart of the Crucifixion of the West. The Buddha beneath the Tree of Enlightenment (the Bo Tree) and Christ on the Holy Rood (the Tree of Redemption) are analogous figures, incorporating an archetypal World Savior, World Tree motif, which is of immemorial antiquity. Many other variants of the theme will be found among the episodes to come. The Immovable Spot and Mount Cavalry are images of the World Navel, or World Axis.

Note 28: The point is that Buddahood, Enlightenment, cannot be communicated, but only the WAY to Enlightenment.

As we soon shall see, whether presented in the vast, almost oceanic images of the Orient, in the vigorous narratives of the Greeks, or in the majestic legends of the Bible, the adventure of the hero normally follows the pattern of the nuclear unit above described: a separation from the world, a penetration to some source of power, and a life-enhancing return. The whole of the Orient has been blessed by the boon brought back by Gautama Buddha—his wonderful teaching of the Good Law—just as the Occident has been by the Decalogue of Moses. The Greeks referred fire, the first support of all human culture, to the world-transcending deed of their Prometheus, and the Romans the founding of their world-supporting city to Aeneas, following his departure from fallen Troy and his visit to the eerie underworld of the dead. Everywhere, no matter what the sphere of interest (whether religious, political, or personal), the really creative acts are represented as those deriving from some sort of dying to the world; and what happens in the interval of the hero’s nonentity, so that he comes back as one reborn, made great and filled with creative power, mankind is also unanimous in declaring.

The first great stage, that of the separation or departure, will be shown in Part I, Chapter I, in five subsections: (1) “The Call to Adventure,” or the signs of the vocation of the hero; (2) “Refusal of the Call,” or the folly of the flight from the god; (3) “Supernatural Aid,” the unsuspected assistance that comes to one who has undertaken his proper adventure; (4) “The Crossing of the First Threshold;” and (5) “The Belly of the Whale,” or the passage into the realm of night. The stage of the trials and victories of initiation will appear in Chapter II in six subsections: (1) “The Road of Trials,” or the dangerous aspect of the gods; (2) “The Meeting with the Goddess” (Magna Mater), or the bliss of infancy regained; (3) “Woman as the Temptress,” the realization and agony of Oedipus; (4) “Atonement with the Father;” (5) “Apotheosis;” and (6) “The Ultimate Boon.”

The third of the following chapters will conclude the discussion of these prospects under six subheadings: (1) “Refusal of the Return,” or the world denied; (2) “The Magic Flight,” or the escape of Prometheus; (3) “Rescue from Without;” (4) “The Crossing of the Return Threshold,” or the return to the world of common day; (5) “Master of the Two Worlds;” and (6) “Freedom to Live,” the nature and function of the ultimate boon.

Tribal or local heroes, such as the emperor Huang Ti, Moses, or the Aztec Tezcatlipoca, commit their boons to a single folk; universal heroes—Mohammed, Jesus, Gautama Buddha-bring a message for the entire world.

Part II, “The Cosmogonie Cycle,” unrolls the great vision of the creation and destruction of the world which is vouchsafed as revelation to the successful hero. Chapter I, Emanations, treats of the coming of the forms of the universe out of the void. Chapter II, The Virgin Birth, is a review of the creative and redemptive roles of the female power, first on a cosmic scale as the Mother of the Universe, then again on the human plane as the Mother of the Hero. Chapter III, Transformations of the Hero, traces the course of the legendary history of the human race through its typical stages, the hero appearing on the scene in various forms according to the changing needs of the race. And Chapter IV, Dissolutions, tells of the foretold end, first of the hero, then of the manifested world.

The cosmogonie cycle is presented with astonishing consistency in the sacred writings of all the continents,43 and it gives to the adventure of the hero a new and interesting turn; for now it appears that the perilous journey was a labor not of attainment but of reattainment, not discovery but rediscovery. The godly powers sought and dangerously won are revealed to have been within the heart of the hero all the time.

The two—the hero and his ultimate god, the seeker and the found—are thus understood as the outside and inside of a single, self-mirrored mystery, which is identical with the mystery of the manifest world. The great deed of the supreme hero is to come to the knowledge of this unity in multiplicity and then to make it known.

1 The World Navel

THE effect of the successful adventure of the hero is the unlocking and release again of the flow of life into the body of the world. The miracle of this flow may be represented in physical terms as a circulation of food substance, dynamically as a streaming of energy, or spiritually as a manifestation of grace. Such varieties of image alternate easily, representing three degrees of condensation of the one life force. An abundant harvest is the sign of God’s grace; God’s grace is the food of the soul; the lightning bolt is the harbinger of fertilizing rain, and at the same time the manifestation of the released energy of God. Grace, food substance, energy: these pour into the living world, and wherever they fail, life decomposes into death.

The torrent pours from an invisible source, the point of entry being the center of the symbolic circle of the universe, the Immovable Spot of the Buddha legend,46 around which the world may be said to revolve. Beneath this spot is the earth-supporting head of the cosmic serpent, the dragon, symbolical of the waters of the abyss, which are the divine life-creative energy and substance of the demiurge, the world-generative aspect of immortal being.47 The tree of life, i.e., the universe itself, grows from this point. It is rooted in the supporting darkness; the golden sun bird perches on its peak; a spring, the inexhaustible well, bubbles at its foot.

Thus the World Navel is the symbol of the continuous creation

The dome of heaven rests on the quarters of the earth, sometimes supported by Jour çaryatidal kings, dwarfs, giants, elephants, or turtles.

The hearth in the home, the altar in the temple, is the hub of the wheel of the earth, the womb of the Universal Mother whose fire is the fire of life.

The solar ray igniting the hearth symbolizes the communication of divine energy to the womb of the world—and is again the axis uniting and turning the two wheels.

Wherever a hero has been born, has wrought, or has passed back into the void, the place is marked and sanctified. A temple is erected there to signify and inspire the miracle of perfect centeredness; for this is the place of the breakthrough into abundance. Someone at this point discovered eternity. The site can serve, therefore, as a support for fruitful meditation. Such temples are designed, as a rule, to simulate the four directions of the world horizon, the shrine or altar at the center being symbolical of the Inexhaustible Point. The one who enters the temple compound and proceeds to sanctuary is imitating the deed of the original hero. His aim is to rehearse the universal pattern as a means of evoking within himself the recollection of the life-centering, life-renewing form.

Because, finally, the All is everywhere, and anywhere may become the seat of power.

The World Navel, then, is ubiquitous. And since it is the source of all existence, it yields the world’s plenitude of both good and evil. Ugliness and beauty, sin and virtue, pleasure and pain, are equally its production.

Chapter 1. Departure

- The Call to Adventure

This is an example of one of the ways in which the adventure can begin. A blunder apparently the merest chance—reveals an unsuspected world, and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood. As Freud has shown,2 blunders are not the merest chance. They are the result of suppressed desires and conflicts.

…it marks what has been termed “the awakening of the self.”

Typical of the circumstances of the call are the dark forest, the great tree, the babbling spring, and the loathly, underestimated appearance of the carrier of the power of destiny. We recognize in the scene the symbols of the World Navel.

Freud has suggested that all moments of anxiety reproduce the painful feelings of the first separation from the mother—the tightening of the breath, congestion of the blood, etc., of the crisis of birth.4 Conversely, all moments of separation and new birth produce anxiety.

The disgusting and rejected frog or dragon of the fairy tale brings up the sun ball in its mouth; for the frog, the serpent, the rejected one, is the representative of that unconscious deep (“so deep that the bottom cannot be seen”) wherein are hoarded all of the rejected, unadmitted, unrecognized, unknown, or undeveloped factors, laws, and elements of existence.

The herald or announcer of the adventure, therefore, is often dark, loathly, or terrifying, judged evil by the world; yet if one could follow the way would be opened through the walls of day into the dark where the jewels glow. Or the herald is a beast (as in the fairy tale), representative of the repressed instinctual fecundity within ourselves, or again a veiled mysterious figure—the unknown.

Whether dream or myth, in these adventures there is an atmosphere of irresistible fascination about the figure that appears suddenly as guide, marking a new period, a new stage, in the biography. That which has to be faced, and is somehow profoundly familiar to the unconscious—though unknown, surprising, and even frightening to the conscious personality—makes itself known; and what formerly was meaningful may become strangely emptied of value: like the world of the king’s child, with the sudden disappearance into the well of the golden ball. Thereafter, even though the hero returns for a while to his familiar occupations, they may be found unfruitful

This first stage of the mythological journey—which we have designated the “call to adventure”—signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown.

This fateful region of both treasure and danger may be variously represented: as a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, superhuman deeds, and impossible delight. The hero can go forth of his own volition to accomplish the adventure, as did Theseus when he arrived in his father’s city, Athens, and heard the horrible history of the Minotaur; or he may be carried or sent abroad by some benign or malignant agent, as was Odysseus, driven about the Mediterranean by the winds of the angered god, Poseidon. The adventure may begin as a mere blunder, as did that of the princess of the fairy tale; or still again, one may be only casually strolling, when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man. Examples might be multiplied, ad infinitum, from every corner of the world.

2. Refusal of the Call

Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative. Walled in boredom, hard work, or “culture,” the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved.

Whatever house he builds, it will be a house of death: a labyrinth of cyclopean walls to hide from him his Minotaur. All he can do is create new problems for himself and await the gradual approach of his disintegration.

The myths and folk tales of the whole world make clear that the refusal is essentially a refusal to give up what one takes to be one’s own interest.

One is harassed, both day and night, by the divine being that is the image of the living self within the locked labyrinth of one’s own disoriented psyche. The ways to the gates have all been lost: there is no exit. One can only cling, like Satan, furiously, to oneself and be in hell; or else break, and be annihilate at last, in God.

What they represent is an impotence to put off the infantile ego, with its sphere of emotional relationships and ideals. One is bound in by the walls of childhood; the father and mother stand as threshold guardians, and the timorous soul, fearful of some punishment, fails to make the passage through the door and come to birth in the world without.

Sometimes the predicament following an obstinate refusal of the call proves to be the occasion of a providential revelation of some unsuspected principle of release.

3. Supernatural Aid

FOR those who have not refused the call, the first encounter of the hero-journey is with a protective figure (often a little old crone or old man) who provides the adventurer with amulets against the dragon forces he is about to pass.

The helpful crone and fairy godmother is a familiar feature of European fairy lore; in Christian saints’ legends the role is commonly played by the Virgin. The Virgin by her intercession can win the mercy of the Father. Spider Woman with her web can control the movements of the Sun. The hero who has come under the protection of the Cosmic Mother cannot be harmed. The thread of Ariadne brought Theseus safely through the adventure of the labyrinth.

What such a figure represents is the benign, protecting power of destiny. The fantasy is a reassurance—a promise that the peace of Paradise, which was known first within the mother womb, is not to be lost; that it supports the present and stands in the future as well as in the past (is omega as well as alpha); that though omnipotence may seem to be endangered by the threshold passages and life awakenings, protective power is always and ever present within the sanctuary of the heart and even immanent within, or just behind, the unfamiliar features of the world. One has only to know and trust, and the ageless guardians will appear. Having responded to his own call, and continuing to follow courageously as the consequences unfold, the hero finds all the forces of the unconscious at his side.

Not infrequently, the supernatural helper is masculine in form. In fairy lore it may be some little fellow of the wood, some wizard, hermit, shepherd, or smith, who appears, to supply the amulets and advice that the hero will require. The higher mythologies develop the role in the great figure of the guide, the teacher, the ferryman, the conductor of souls to the afterworld.

Goethe presents the masculine guide in Faust as Mephi-stopheles—and not infrequently the dangerous aspect of the “mercurial” figure is stressed; for he is the lurer of the innocent soul into realms of trial.

Protective and dangerous, motherly and fatherly at the same time, this supernatural principle of guardianship and direction unites in itself all the ambiguities of the unconscious—thus signifying the support of our conscious personality by that other, larger system, but also the inscrutability of the guide that we are following, to the peril of all our rational ends.

The call, in fact, was the first announcement of the approach of this initiatory priest.

Note 33: The well is symbolical of the unconscious. Compare that of the fairy story of the Frog King.

4. The Crossing of the First Threshold

WITH the personifications of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the “threshold guardian” at the entrance to the zone of magnified power. Such custodians bound the world in the four directions—also up and down—standing for the limits of the hero’s present sphere, or life horizon. Beyond them is darkness, the unknown, and danger; just as beyond the parental watch is danger to the infant and beyond the protection of his society danger to the member of the tribe.

The folk mythologies populate with deceitful and dangerous presences every desert place outside the normal traffic of the village.

The regions of the unknown (desert, jungle, deep sea, alien land, etc.) are free fields for the projection of unconscious content. Incestuous libido and patricidal destrudo are thence reflected back against the individual and his society in forms suggesting threats of violence and fancied dangerous delight—not only as ogres but also as sirens of mysteriously seductive, nostalgic beauty.

The Arcadian god Pan is the best known Classical example of this dangerous presence dwelling just beyond the protected zone of the village boundary.

This is a dream that brings out the sense of the first, or protective, aspect of the threshold guardian. One had better not challenge the watcher of the established bounds. And yet—it is only by advancing beyond those bounds, provoking the destructive other aspect of the same power, that the individual passes, either alive or in death, into a new zone of experience

The “Wall of Paradise,” which conceals God from human sight, is described by Nicholas of Cusa as constituted of the “coincidence of opposites,” its gate being guarded by “the highest spirit of reason, who bars the way until he has been overcome.”53 The pairs of opposites (being and not being, life and death, beauty and ugliness, good and evil, and all the other polarities that bind the faculties to hope and fear, and link the organs of action to deeds of defense and acquisition) are the clashing rocks (Symplegades) that crush the traveler, but between which the heroes always pass. This is a motif known throughout the world.

5. The Belly of the Whale

THE idea that the passage of the magical threshold is a transit into a sphere of rebirth is symbolized in the worldwide womb image of the belly of the whale. The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown, and would appear to have died.

The little German girl, Red Ridinghood, was swallowed by a wolf. The Polynesian favorite, Maui, was swallowed by his great-great-grandmother, Hine-nui-te-po. And the whole Greek pantheon, with the sole exception of Zeus, was swallowed by its father, Kronos.

This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form oE self-annihilation. Its resemblance to the adventure of the Symplegades is obvious. But here, instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again. The disappearance corresponds to the passing of a worshiper into a temple—where he is to be quickened by the recollection of who and what he is, namely dust and ashes unless immortal. The temple interior, the belly of the whale, and the heavenly land beyond, above, and below the confines of the world, are one and the same. That is why the approaches and entrances to temples are flanked and defended by colossal gargoyles: dragons, lions, devil-slayers with drawn swords, resentful dwarfs, winged bulls. These are the threshold guardians to ward away all incapable of encountering the higher silences within. They are preliminary embodiments of the dangerous aspect of the presence, corresponding to the mythological ogres that bound the conventional world, or to the two rows of teeth of the whale. They illustrate the fact that the devotee at the moment of entry into a temple undergoes a metamorphosis. His secular character remains without; he sheds it, as a snake its slough. Once inside he may be said to have died to time and returned to the World Womb, the World Navel, the Earthly Paradise. The mere fact that anyone can physically walk past the temple guardians does not invalidate their significance; for if the intruder is incapable of encompassing the sanctuary, then he has effectually remained without. Anyone unable to understand a god sees it as a devil and is thus defended from the approach. Allegorically, then, the passage into a temple and the hero-dive through the jaws of the whale are identical adventures, both denoting, in picture language, the life-centering, life-renewing act.

The hero whose attachment to ego is already annihilate passes back and forth across the horizons of the world, in and out of the

dragon, as readily as a king through all the rooms of his house. And therein lies his power to save; for his passing and returning demonstrate that through all the contraries of phenomenality the Un-create-Imperishable remains, and there is nothing to fear. And so it is that, throughout the world, men whose function it has been to make visible on earth the life-fructifying mystery of the slaying of the dragon have enacted upon their own bodies the great symbolic act, scattering their flesh, like the body of Osiris, for the renovation of the world.

CHAPTER II INITIATION

1 The Road of Trials

ONCE having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials.

The hero is covertly aided by the advice, amulets, and secret agents of the supernatural helper whom he met before his entrance into this region. Or it may be that he here discovers for the first time that there is a benign power everywhere supporting him in his superhuman passage.

…the “difficult tasks” motif is that of Psyche’s quest for her lost lover, Cupid.1 Here all the principal roles are reversed: instead of the lover trying to win his bride, it is the bride trying to win her lover; and instead of a cruel father withholding his daughter from the lover, it is the jealous mother, Venus, hiding her son, Cupid, from his bride.

Psyche’s voyage to the underworld is but one of innumerable such adventures undertaken by the heroes of fairy tale and myth. Among the most perilous are those of the shamans of the peoples of the farthest north (the Lapps, Siberians, Eskimo, and certain American Indian tribes), when they go to seek out and recover the lost or abducted souls of the sick.

In every primitive tribe,” writes Dr. Géza Róheim, “we find the medicine man in the center of society and it is easy to show that the medicine man is either a neurotic or a psychotic or at least that his art is based on the same mechanisms as a neurosis or a psychosis. Human groups are actuated by their group ideals, and these are always based on the infantile situation.” “The infancy situation is modified or inverted by the process of maturation, again modified by the necessary adjustment to reality, yet it is there and supplies those unseen libidinal ties without which no human groups could exist.”6 The medicine men, therefore, are simply making both visible and public the systems of symbolic fantasy that are present in the psyche of every adult member of their society. “They are the leaders in this infantile game and the lightning conductors of common anxiety. They fight the demons so that others can hunt the prey and in general fight reality.”

And so it happens that if anyone—in whatever society—undertakes for himself the perilous journey into the darkness by descending, either intentionally or unintentionally, into the crooked lanes of his own spiritual labyrinth, he soon finds himself in a landscape of symbolical figures (any one of which may swallow him) which is no less marvelous than the wild Siberian world of the pudak and sacred mountains. In the vocabulary of the mystics, this is the second stage of the Way, that of the “purification of the self,” when the senses are “cleansed and humbled,” and the energies and interests “concentrated upon transcendental things;”8 or in a vocabulary of more modern turn: this is the process of dissolving, transcending, or transmuting the infantile images of our personal past.

There can be no question: the psychological dangers through which earlier generations were guided by the symbols and spiritual exercises of their mythological and religious inheritance, we today (in so far as we are unbelievers, or, if believers, in so far as our inherited beliefs fail to represent the real problems of contemporary life) must face alone, or, at best, with only tentative, impromptu, and not often very effective guidance. This is our problem as modern, “enlightened” individuals, for whom all gods and devils have been rationalized out of existence.

To hear and profit, however, one may have to submit somehow to purgation and surrender. And that is part of our problem: just how to do that.

The oldest recorded account of the passage through the gates of metamorphosis is the Sumerian myth of the goddess Inanna’s descent to the nether world.

From the “great above” she set her mind toward

the “great below,”

The goddess, from the “great above” she set her

mind toward the “great below,”

Inanna, from the “great above” she set her mind

toward the “great below.”

My lady abandoned heaven, abandoned earth,

To the nether world she descended,

Inanna abandoned heaven, abandoned earth,

To the nether world she descended,

Abandoned lordship, abandoned ladyship,

To the nether world she descended.

Inanna and Ereshkigal, the two sisters, light and dark respectively, together represent, according to the antique manner of symbolization, the one goddess in two aspects; and their confrontation epitomizes the whole sense of the difficult road of trials. The hero, whether god or goddess, man or woman, the figure in a myth or the dreamer of a dream, discovers and assimilates his opposite (his own unsuspected self) either by swallowing it or by being swallowed. One by one the resistances are broken. He must put aside his pride, his virtue, beauty, and life, and bow or submit to the absolutely intolerable. Then he finds that he and his opposite are not of differing species, but one flesh.

Can the ego put itself to death? For many-headed is this surrounding Hydra; one head cut off, two more appear—unless the right caustic is applied to the mutilated stump.

2. The Meeting with the Goddess

THE ultimate adventure, when all the barriers and ogres have been overcome, is commonly represented as a mystical marriage of the triumphant hero-soul with the Queen Goddess of the World. This is the crisis at the nadir, the zenith, or at the uttermost edge of the earth, at the central point of the cosmos, in the tabernacle of the temple, or within the darkness of the deepest chamber of the heart.

The Lady of the House of Sleep is a familiar figure in fairy tale and myth. We have already spoken of her, under the forms of Brynhild and little Briar-rose. She is the paragon of all paragons of beauty, the reply to all desire, the bliss-bestowing goal of every hero’s earthly and unearthly quest. She is mother, sister, mistress, bride. Whatever in the world has lured, whatever has seemed to promise joy, has been premonitory of her existence—in the deep of sleep, if not in the cities and forests of the world. For she is the incarnation of the promise of perfection; the soul’s assurance that, at the conclusion of its exile in a world of organized inadequacies, the bliss that once was known will be known again: the comforting, the nourishing, the “good” mother—young and beautiful—who was known to us, and even tasted, in the remotest past. Time sealed her away, yet she is dwelling still, like one who sleeps in timelessness, at the bottom of the timeless sea.

The remembered image is not only benign, however; for the “bad” mother too—(1) the absent, unattainable mother, against whom aggressive fantasies are directed, and from whom a counter-aggression is feared; (2) the hampering, forbidding, punishing mother; (3) the mother who would hold to herself the growing child trying to push away; and finally (4) the desired but forbidden mother (Oedipus complex) whose presence is a lure to dangerous desire (castration complex)—persists in the hidden land of the adult’s infant recollection and is sometimes even the greater force. She is at the root of such unattainable great goddess figures as that of the chaste and terrible Diana—whose absolute ruin of the young sportsman Actaeon illustrates what a blast of fear is contained in such symbols of the mind’s and body’s blocked desire.

The mythological figure of the Universal Mother imputes to the cosmos the feminine attributes of the first, nourishing and protecting presence. The fantasy is primarily spontaneous; for there exists a close and obvious correspondence between the attitude of the young child toward its mother and that of the adult toward the surrounding material world.

For she is the world creatrix, ever mother, ever virgin. She encompasses the encompassing, nourishes the nourishing, and is the life of everything that lives.

She is also the death of everything that dies. The whole round of existence is accomplished within her sway, from birth, through adolescence, maturity, and senescence, to the grave. She is the womb and the tomb: the sow that eats her farrow. Thus she unites the “good” and the “bad,” exhibiting the two modes of the remembered mother, not as personal only, but as universal. The devotee is expected to contemplate the two with equal equanimity. Through this exercise his spirit is purged of its infantile, inappropriate sentimentalities and resentments, and his mind opened to the inscrutable presence which exists, not primarily as “good” and “bad” with respect to his childlike human convenience, his weal and woe, but as the law and image of the nature of being.

Her name is Kali, the Black One; her title: The Ferry across the Ocean of Existence.

Woman, in the picture language of mythology, represents the totality of what can be known. The hero is the one who comes to know.

The meeting with the goddess (who is incarnate in every woman) is the final test of the talent of the hero to win the boon of love (charity: amorfati), which is life itself enjoyed as the encasement of eternity.

And when the adventurer, in this context, is not a youth but a maid, she is the one who, by her qualities, her beauty, or her yearning, is fit to become the consort of an immortal. Then the heavenly husband descends to her and conducts her to his bed—whether she will or no. And if she has shunned him, the scales fall from her eyes; if she has sought him, her desire finds its peace.

The Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches celebrate the same mystery in the Feast of the Assumption: “The Virgin Mary is taken up into the bridal chamber of heaven, where the King of Kings sits on his starry throne.” “O Virgin most prudent, whither goest thou, bright as the morn? all beautiful and sweet art thou, O daughter of Zion, fair as the moon, elect as the sun.”

3. Woman as the Temptress

THE mystical marriage with the queen goddess of the world represents the hero’s total mastery of life; for the woman is life, the hero its knower and master. And the testings of the hero, which were preliminary to his ultimate experience and deed, were symbolical of those crises of realization by means of which his consciousness came to be amplified and made capable of enduring the full possession of the mother-destroyer, his inevitable bride. With that he knows that he and the father are one: he is in the father’s place.

The whole sense of the ubiquitous myth of the hero’s passage is that it shall serve as a general pattern for men and women, wherever they may stand along the scale. Therefore it is formulated in the broadest terms. The individual has only to discover his own position with reference to this general human formula, and let it then assist him past his restricting walls. Who and where are his ogres? Those are the reflections of the unsolved enigmas of his own humanity. What are his ideals? Those are the symptoms of his grasp of life.

The crux of the curious difficulty lies in the fact that our conscious views of what life ought to be seldom correspond to what life really is. Generally we refuse to admit within ourselves, or within our friends, the fullness of that pushing, self protective, malodorous, carnivorous, lecherous fever which is the very nature of the organic cell. Rather, we tend to perfume, whitewash, and reinterpret; meanwhile imagining that all the flies in the ointment, all the hairs in the soup, are the faults of some unpleasant someone else.

4. Atonement with the Father

…the ogre aspect of the father.

In most mythologies, the images of mercy and grace are rendered as vividly as those of justice and wrath, so that a balance is maintained, and the heart is buoyed rather than scourged along its way. “Fear not!” says the hand gesture of the god Shiva, as he dances before his devotee the dance of the universal destruction.

For the ogre aspect of the father is a reflex of the victim’s own ego—derived from the sensational nursery scene that has been left behind, but projected before; and the fixating idolatry of that pedagogical nonthing is itself the fault that keeps one steeped in a sense of sin, sealing the potentially adult spirit from a better balanced, more realistic view of the father, and therewith of the world. Atonement (at-one-ment) consists in no more than the abandonment of that self-generated double monster—the dragon thought to be God superego) and the dragon thought to be Sin (repressed id). But this requires an abandonment of the attachment to ego itself, and that is what is difficult. One must have a faith that the father is merciful, and then a reliance on that mercy. Therewith, the center of belief is transferred outside of the bedeviling god’s tight scaly ring, and the dreadful ogres dissolve.

It is in this ordeal that the hero may derive hope and assurance from íhe helpful female figure, by whose magic (pollen charms or power of intercession) he is protected through all the frightening experiences of the father’s ego-shattering initiation. For if it is impossible to trust the terrifying father-face, then one’s faith must be centered elsewhere (Spider Woman, Blessed Mother); and with that reliance for support, one endures the crisis—only to find, in the end, that the father and mother reflect each other, and are in essence the same.

The need for great care on the part of the father, admitting to his house only those who have been thoroughly tested, is illustrated by the unhappy exploit of the lad Phaëthon, described in a famous tale of the Greeks. Born of a virgin in Ethiopia and taunted by his playmates to search the question of his father, he set off across Persia and India to find the palace of the Sun—for his mother had told him that his father was Phoebus, the god who drove the solar chariot.

This tale of indulgent parenthood illustrates the antique idea that when the roles of life aie assumed by the improperly initiated, chaos supervenes. When the child outgrows the popular idyl of the mother breast and turns to face the world of specialized adult action, it passes, spiritually, into the sphere of the father—who becomes, for his son, the sign of the future task, and for his daughter, of the future husband. Whether he knows it or not, and no matter what his position in society, the father is the initiating priest through whom the young being passes on into the larger world. And just as, formerly, the mother represented the “good” and “evil,” so now does he, but with this complication—that there is a new element of rivalry in the picture: the son against the father for the mastery of the universe, and the daughter against the mother to be the mastered world.

The traditional idea of initiation combines an introduction of the candidate into the techniques, duties, and prerogatives of his vocation with a radical readjustment of his emotional relationship to the parental images. The mystagogue (father or father-substitute) is to entrust the symbols of office only to a son who has been effectually purged of all inappropriate infantile cathexes—for whom the just, impersonal exercise of the powers will not be rendered impossible by unconscious (or perhaps even conscious and rationalized) motives of self aggrandizement, personal preference, or resentment. Ideally, the invested one has been divested of his mere humanity and is representative of an impersonal cosmic force. He is the twice-born: he has become himself the father. And he is competent, consequently, now to enact himself the role of the initiator, the guide, the sun door, through whom one may pass from the infantile illusions of “good” and “evil” to an experience of the majesty of cosmic law, purged of hope and fear, and at peace in the understanding of the revelation of being.

…through the Christian church (in the mythology of the Fall and Redemption, Crucifixion and Resurrection, the “second birth” of baptism, the initiatory blow on the cheek at confirmation, the symbolical eating of the Flesh and drinking of the Blood) solemnly, and sometimes effectively, we are united to those immortal images of initiatory might, through the sacramental operation of which, man, since the beginning of his day on earth, has dispelled the terrors of his phenomenality and won through to the all-transfiguring vision of immortal being. “For if the blood of bulls and of goats, and the ashes of an heifer sprinkling the unclean, sanctifieth to the purifying of the flesh: how much more shall the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without spot to God, purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living God?”

But the most extraordinary and profoundly moving of the traits of Viracocha, this nobly conceived Peruvian rendition of the universal god, is the detail that is peculiarly his own, namely that of the tears. The living waters are the tears of God. Herewith the world-discrediting insight of the monk, “All life is sorrowful,” is combined with the world-begetting affirmative of the father: “Life must bei” In full awareness of the life anguish of the creatures of his hand, in full consciousness of the roaring wilderness of pains, the brain-splitting fires of the deluded, self-ravaging, lustful, angry universe of his creation, this divinity acquiesces in the deed of supplying life to life. To withhold the seminal waters would be to annihilate; yet to give them forth is to create this world that we know. For the essence of time is flux, dissolution of the momentarily existent; and the essence of life is time. In his mercy, in his love for the forms of time, this demiurgic man of men yields countenance to the sea of pangs; but in his full awareness of what he is doing, the seminal waters of the life that he gives are the tears of his eyes.

The paradox of creation, the coming of the forms of time out of eternity, is the germinal secret of the father. It can never be quite explained. Therefore, in every system of theology there is an umbilical point, an Achilles tendon which the finger of mother life has touched, and where the possibility of perfect knowledge has been impaired. The problem of the hero is to pierce himself (and therewith his world) precisely through that point; to shatter and annihilate that key knot of his limited existence.

The problem of the hero going to meet the father is to open his soul beyond terror to such a degree that he will be ripe to understand how the sickening and insane tragedies of this vast and ruthless cosmos are completely validated in the majesty of Being. The hero transcends life with its peculiar blind spot and for a moment rises to a glimpse of the source. He beholds the face of the father, understands—and the two are atoned.

5. Apotheosis

When the envelopment of consciousness has been annihilated, then he becomes free of all fear, beyond the reach of change.”84 This is the release potential within us all, and which anyone can attain—through herohood; for, as we read: “All things are Buddha-things;”85 or again (and this is the other way of making the same statement): “All beings are without self.”

Time and eternity are two aspects of the same experience-whole, two planes of the same nondual ineffable; i.e., the jewel of eternity is in the lotus of birth and death: om mani padme hum. The first wonder to be noted here is the androgynous character of the Bodhisattva: masculine Avalokiteshvara, feminine Kwan Yin. Male-female gods are not uncommon in the world of myth. They emerge always with a certain mystery; for they conduct the mind beyond objective experience into a symbolic realm where duality is left behind.

And among the Greeks, not only Hermaphrodite (the child of Hermes and Aphrodite),88 but Eros too, the divinity of love (the first of the gods, according to Plato),89 were in sex both female and male.

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.”90 The question may arise in the mind as to the nature of the image of God; but the answer is already given in the text, and is clear enough. “When the Holy One, Blessed be He, created the first man, He created him androgynous.”91 The removal of the feminine into another form symbolizes the beginning of the fall from perfection into duality; and it was naturally followed by the discovery of the duality of good and evil, exile from the garden where God walks on earth, and thereupon the building of the wall of Paradise, constituted of the “coincidence of opposites,”92 by which Man (now man and woman) is cut off from not only the vision but even the recollection of the image of God.

This is the Biblical version of a myth known to many lands. It represents one of the basic ways of symbolizing the mystery of creation: the devolvement of eternity into time, the breaking of the one into the two and then the many, as well as the generation of new life through the reconjunction of the two. This image stands at the beginning of the cosmogonie cycle,93 and with equal propriety at the conclusion of the hero-task, at the moment when the wall of Paradise is dissolved, the divine form found and recollected, and wisdom regained.

The call of the Great Father Snake was alarming to the child; the mother was protection. But the father came. He was the guide and initiator into the mysteries of the unknown. As the original intruder into the paradise of the infant with its mother, the father is the archetypal enemy; hence, throughout life all enemies are symbolical (to the unconscious) of the father.

…the irresistible compulsion to make war: the impulse to destroy the father is continually transforming itself into public violence. The old men of the immediate community or race protect themselves from their growing sons by the psychological magic of their totem ceremonials. They enact the ogre father, and then reveal themselves to be the feeding mother too. A new and larger paradise is thus established. But this paradise does not include the traditional enemy tribes, or races, against whom aggression is still systematically projected.

The rest of the world meanwhile (that is to say, by far the greater portion of mankind) is left outside the sphere of his sympathy and protection because outside the sphere of the protection of his god. And there takes place, then, that dramatic divorce of the two principles of love and hate which the pages of history so bountifully illustrate. Instead of clearing his own heart the zealot tries to clear the world. The laws of the City of God are applied only to his in-group (tribe, church, nation, class, or what not) while the fire of a perpetual holy war is hurled (with good conscience, and indeed a sense of pious service) against whatever uncircumcised, barbarian, heathen, “native,” or alien people happens to occupy the position of neighbor.

Once we have broken free of the prejudices of our own provincially limited ecclesiastical, tribal, or national rendition of the world archetypes, it becomes possible to understand that the supreme initiation is not that of the local motherly fathers, who then project aggression onto the neighbors for their own defense.

The good news, which the World Redeemer brings and which so many have been glad to hear, zealous to preach, but reluctant, apparently, to demonstrate, is that God is love, that He can be, and is to be, loved, and that all without exception are his children.

The understanding of the final—and critical—implications of the world-redemptive words and symbols of the tradition of Christendom has been so disarranged, during the tumultuous centuries that have elapsed since St. Augustine’s declaration of the holy war of the Civitas Dei against the Civitas Diaboli, that the modern thinker wishing to know the meaning of a world religion (i.e., of a doctrine of universal love) must turn his mind to the other great (and much older) universal communion: that of the Buddha, where the primary word still is peace—peace to all beings.

If ye realize the Emptiness of All Things, Compassion

will arise within your hearts;

If ye lose all differentiation between yourselves and others, fit

to serve others ye will be;

And when in serving others ye shall win success, then shall ye

meet with me;

And finding me, ye shall attain to Buddhahood.

Peace is at the heart of all because Avalokiteshvara-Kwannon, the mighty Bodhisattva, Boundless Love, includes, regards, and dwells within (without exception) every sentient being.

The Lord Who is Seen Within.” We are all reflexes of the image of the Bodhisattva. The sufferer within us is that divine being. We and that protecting father are one. This is the redeeming insight. That protecting father is every man we meet. And so it must be known that, though this ignorant, limited, self-defending, suffering body may regard itself as threatened by some other the enemy—that one too is the God. The ogre breaks us, but the hero, the fit candidate, undergoes the initiation “like a man;” and behold, it was the father: we in Him and He in us. The dear, protecting mother of our body could not defend us from the Great Father Serpent; the mortal, tangible body that she gave us was delivered into his frightening power. But death was not the end. New life, new birth, new knowledge of existence (so that we live not in this physique only, but in all bodies, all physiques of the world, as the Bodhisattva) was given us. That father was himself the womb, the mother, of a second birth.

The childhood parent images and ideas of “good” and “evil” have been surpassed. We no longer desire and fear; we are what was desired and feared. All the gods, Bodhisattvas, and Buddhas have been subsumed in us, as in the halo of the mighty holder of the lotus of the world.

The method of the celebrated Buddhist Eightfold Path:

Right Belief, Right Intentions,

Right Speech, Right Actions,

Right Livelihood, Right Endeavoring,

Right Mindfulness, Right Concentration.

And the Christian reading of the meaning also is the same: Et Verbum caro factum est, i.e., “The Jewel is in the Lotus”: Om mani padme Aum.

Note 134: “And the Word was made flesh”; verse of the Angelus, celebrating the conception of Jesus in Mary’s womb.

6. The Ultimate Boon

The motif (derived from an infantile fantasy) of the inexhaustible dish, symbolizing the perpetual life-giving, form-building powers of the universal source, is a fairy-tale counterpart of the mythological image of the cornucopian banquet of the gods.

The profession, for example, of the medicine man, this nucleus of all primitive societies, “originates … on the basis of the infantile body-destruction fantasies, by means of a series of defence mechanisms.”139 In Australia a basic conception is that the spirits have removed the intestines of the medicine man and substituted pebbles, quartz crystals, a quantity of rope, and sometimes also a little snake endowed with power.140 “The first formula is abreaction in fantasy (my inside has already been destroyed) followed by reaction-formation (my inside is not something corruptible and full of faeces, but incorruptible, full of quartz crystals.

The supreme boon desired for the Indestructible Body is uninterrupted residence in the Paradise of the Milk that Never Fails

Soul and body food, heart’s ease, is the gift of “All Heal,” the nipple inexhaustible. Mt. Olympus rises to the heavens; gods and heroes banquet there on ambrosia (α, not, mortal). In Wotan’s mountain hall, four hundred and thirty-two thousand heroes consume the undiminished flesh of Sachrimnir, the Cosmic Boar, washing it down with a milk that runs from the udders of the she-goat Heidrun: she feeds on the leaves of Yggdrasil, the World Ash. Within the fairy hills of Erin, the deathless Tuatha De Danaan consume the self-renewing pigs of Manannan, drinking copiously of Guibne’s ale. In Persia, the gods in the mountain garden on Mt. Hara Berezaiti drink immortal haoma, distilled from the Gaokerena Tree, the tree of life. The Japanese gods drink sake, the Polynesian ave, the Aztec gods drink the blood of men and maids. And the redeemed of Yahweh, in their roof garden, are served the inexhaustible, delicious flesh of the monsters Behemoth, Leviathan, and Ziz, while drinking the liquors of the four sweet rivers of paradise.

Humor is the touchstone of the truly mythological as distinct from the more literal-minded and sentimental theological mood. The gods as icons are not ends in themselves. Their entertaining myths transport the mind and spirit, not up to, but past them, into the yonder void; from which perspective the more heavily freighted theological dogmas then appear to have been only pedagogical lures: their function, to cart the unadroit intellect away from its concrete clutter of facts and events to a comparatively rarefied zone, where, as a final boon, all existence—whether heavenly, earthly, or infernal—may at last be seen transmuted into the semblance of a lightly passing, recurrent, mere childhood dream of bliss and fright.”

The gods and goddesses then are to be understood as embodiments and custodians of the elixir of Imperishable Being but not themselves the Ultimate in its primary state. What the hero seeks through his intercourse with them is therefore not finally themselves, but their grace, i.e., the power of their sustaining substance. This miraculous energy-substance and this alone is the Imperishable; the names and forms of the deities who everywhere embody, dispense, and represent it come and go. This is the miraculous energy of the thunderbolts of Zeus, Yahweh, and the Supreme Buddha, the fertility of the rain of Viracocha, the virtue announced by the bell rung in the Mass at the consecration,157 and the light of the ultimate illumination of the saint and sage. Its guardians dare release it only to the duly proven.

The greatest tale of the elixir quest in the Mesopotamian, pre-Biblical tradition is that of Gilgamesh, a legendary king of the Sumerian city of Erech, who set forth to attain the watercress of immortality, the plant “Never Grow Old.

Now the far land that they were approaching was the residence of Utnapishtim, the hero of the primordial deluge, Gilgamesh, on landing, had to listen to the patriarch’s long recitation of the story of the deluge.

The plant was growing at the bottom of the cosmic sea.

Gilgamesh bathed in a cool water-hole and lay down to rest. But while he slept, a serpent smelled the wonderful perfume of the plant, darted forth, and carried it away. Eating it, the snake immediately gained the power of sloughing its skin, and so renewed its youth. But Gilgamesh, when he awoke, sat down and wept, “and the tears ran down the wall of his nose.”

The research for physical immortality proceeds from a misunderstanding of the traditional teaching. On the contrary, the basic problem is: to enlarge the pupil of the eye, so that the body with its attendant personality will no longer obstruct the view. Immortality is then experienced as a present fact: “It is here! It is here!”

“All things are in process, rising and returning. Plants come to blossom, but only to return to the root. Returning to the root is like seeking tranquility. Seeking tranquility is like moving toward destiny. To move toward destiny is like eternity. To know eternity is enlightenment, and not to recognize eternity brings disorder and evil.

The Japanese have a proverb: “The gods only laugh when men pray to them for wealth.” The boon bestowed on the worshiper is always scaled to his stature and to the nature of his dominant desire: the boon is simply a symbol of life energy stepped down to the requirements of a certain specific case. The irony, of course, lies in the fact that, whereas the hero who has won the favor of the god may beg for the boon of perfect illumination, what he generally seeks are longer years to live, weapons with which to slay his neighbor, or the health of his child.

The agony of breaking through personal limitations is the agony of spiritual growth. Art, literature, myth and cult, philosophy, and ascetic disciplines are instruments to help the individual past his limiting horizons into spheres of ever-expanding realization. As he crosses threshold after threshold, conquering dragon after dragon, the stature of the divinity that he summons to his highest wish increases, until it subsumes the cosmos. Finally, the mind breaks the bounding sphere of the cosmos to a realization transcending all experiences of form—all symbolizations, all divinities: a realization of the ineluctable void.

This is the highest and ultimate crucifixion, not only of the hero, but of his god as well. Here the Son and the Father alike are annihilated—as personality-masks over the unnamed.

…the universal force of a single inscrutable mystery: the power that constructs the atom and controls the orbits of the stars.

That font of life is the core of the individual, and within himself he will find it—if he can tear the coverings away. The pagan Germanic divinity Othin (Wotan) gave an eye to split the veil of light into the knowledge of this infinite dark, and then underwent for it the passion of a crucifixion:

I ween that I hung on the windy tree,

Hung there for nights full nine;

With the spear I was wounded, and offered I was

To Othin, myself to myself,

On the tree that none may ever know

What root beneath it runs.

The Buddha’s victory beneath the Bo Tree is the classic Oriental example of this deed. With the sword of his mind he pierced the bubble of the universe—and it shattered into nought. The whole world of natural experience, as well as the continents, heavens, and hells of traditional religious belief, exploded—together with their gods and demons. But the miracle of miracles was that though all exploded, all was nevertheless thereby renewed, revivified, and made glorious with the effulgence of true being. Indeed, the gods of the redeemed heavens raised their voices in harmonious acclaim of the man-hero who had penetrated beyond them to the void that was their life and source.

CHAPTER III RETURN

1 Refusal of the Return

WHEN the hero—quest has been accomplished, through penetration to the source, or through the grace of some male or female, human or animal, personification, the adventurer still must return with his life-transmuting trophy. The full round, the norm of the monomyth, requires that the hero shall now begin the labor of bringing the runes of wisdom, the Golden Fleece, or his sleeping princess, back into the kingdom of humanity, where the boon may redound to the renewing of the community, the nation, the planet, or the ten thousand worlds.

But the responsibility has been frequently refused. Even the Buddha, after his triumph, doubted whether the message of realization could be communicated, and saints are reported to have passed away while in the supernal ecstasy.

2. The Magic Flight

IF THE hero in his triumph wins the blessing of the goddess or the god and is then explicitly commissioned to return to the world with some elixir for the restoration of society, the final stage of his adventure is supported by all the powers of his supernatural patron. On the other hand, if the trophy has been attained against the opposition of its guardian, or if the hero’s wish to return to the world has been resented by the gods or demons, then the last stage of the mythological round becames a lively, often comical, pursuit.This flight may be complicated by marvels of magical obstruction and evasion.

The flight is a favorite episode of the folk tale, where it is developed under many lively forms.

A popular variety of the magic flight is that in which objects are left behind to speak for the fugitive and thus delay pursuit.

Another well-known variety of the magic flight is one in which a number of delaying obstacles are tossed behind by the wildly fleeing hero.

One of the most shocking of the obstacle flights is that of the Greek hero, Jason. He had set forth to win the Golden Fleece. Putting to sea in the magnificent Argo with a great company of warriors, he had sailed in the direction of the Black Sea, and, though delayed by many fabulous dangers, arrived, at last, miles beyond the Bosporus, at the city and palace of King Aeëtes. Behind the palace was the grove and tree of the dragon-guarded prize.

Now the daughter of the king, Medea, conceived an overpowering passion for the illustrious foreign visitor and, when her father imposed an impossible task as the price of the Golden Fleece, compounded charms that enabled him to succeed.

Then Jason snatched the prize, Medea ran with him, and the Argo put to sea. But the king was soon in swift pursuit. And when Medea perceived that his sails were cutting down their lead, she persuaded Jason to kill Apsyrtos, her younger brother whom she had carried off, and toss the pieces of the dismembered body into the sea. This forced King Aeëtes, her father, to put about, rescue the fragments, and go ashore to give them decent burial. Meanwhile the Argo ran with the wind and passed from his ken.

It is always some little fault, some slight yet critical symptom of human frailty, that makes impossible the open interrelationship between the worlds; so that one is tempted to believe, almost, that if the small, marring accident could be avoided, all would be well.

The myths of failure touch us with the tragedy of life, but those of success only with their own incredibility. And yet, if the mono-myth is to fulfill its promise, not human failure or superhuman success but human success is what we shall have to be shown. That is the problem of the crisis of the threshold of the return. We shall first consider it in the superhuman symbols and then seek the practical teaching for historic man.

3. Rescue from Without

THE hero may have to be brought back from his supernatural adventure by assistance from without. That is to say, the world may have to come and get him.

And yet, in so far as one is alive, life will call. Society is jealous of those who remain away from it, and will come knocking at the door. If the hero—like Muchukunda—is unwilling, the disturber suffers an ugly shock; but on the other hand, if the summoned one is only delayed—sealed in by the beatitude of the state of perfect being (which resembles death)—an apparent rescue is effected, and the adventurer returns.

The mirror, the sword, and the tree, we recognize. The mirror, reflecting the goddess and drawing her forth from the august repose of her divine non-manifestation, is symbolic of the world, the field of the reflected image. Therein divinity is pleased to regard its own glory, and this pleasure is itself inducement to the act of manifestation or “creation.” The sword is the counterpart of the thunderbolt. The tree is the World Axis in its wish-fulfilling, fruitful aspect—the same as that displayed in Christian homes at the season of the winter solstice, which is the moment of the rebirth or return of the sun, a joyous custom inherited from the Germanic paganism that has given to the modern German language its feminine Sonne. The dance of Uzume and the uproar of the gods belong to carnival: the world left topsy-turvy by the withdrawal of the supreme divinity, but joyous for the coming renewal. And the shimenawa, the august rope of straw that was stretched behind the goddess when she reappeared, symbolizes the graciousness of the miracle of the light’s return. This shimenawa is one of the most conspicuous, important, and silently eloquent, of the traditional symbols of the folk religion of Japan. Hung above the entrances of the temples, festooned along the streets at the New Year festival, it denotes the renovation of the world at the threshold of the return. If the Christian cross is the most telling symbol of the mythological passage into the abyss of death, the shimenawa is the simplest sign of the resurrection. The two represent the mystery of the boundary between the worlds—the existent nonexistent line.

Amaterasu is an Oriental sister of the great Inanna, the supreme goddess of the ancient Sumerian cuneiform temple-tablets, whose descent we have already followed into the lower world. Inanna, Ishtar, Astarte, Aphrodite, Venus: those were the names she bore in the successive culture periods of the Occidental development—associated, not with the sun, but with the planet that carries her name, and at the same time with the moon, the heavens, and the fruitful earth. In Egypt she became the goddess of the Dog Star, Sirius, whose annual reappearance in the sky announced the earth-fructifying flood season of the river Nile.

…the rescue from without. They show in the final stages of the adventure the continued operation of the supernatural assisting force that has been attending the elect through the whole course of his ordeal. His consciousness having succumbed, the unconscious nevertheless supplies its own balances, and he is born back into the world from which he came. Instead of holding to and saving his ego, as in the pattern of the magic flight, he loses it, and yet, through grace, it is returned.

This brings us to the final crisis of the round, to which the whole miraculous excursion has been but a prelude—that, namely, of the paradoxical, supremely difficult threshold-crossing of the hero’s return from the mystic realm into the land of common day. Whether rescued from without, driven from within, or gently carried along by the guiding divinities, he has yet to re-enter with his boon the long-forgotten atmosphere where men who are fractions imagine themselves to be complete. He has yet to confront society with his ego-shattering, life-redeeming elixir, and take the return blow of reasonable queries, hard resentment, and good people at a loss to comprehend.

4. The Crossing of the Return Threshold

THE two worlds, the divine and the human, can be pictured only as distinct from each other—different as life and death, as day and night. The hero adventures out of the land we know into darkness; there he accomplishes his adventure, or again is simply lost to us, imprisoned, or in danger; and his return is described as a coming back out of that yonder zone. Nevertheless—and here is a great key to the understanding of myth and symbol—the two kingdoms are actually one. The realm of the gods is a forgotten dimension of the world we know. And the exploration of that dimension, either willingly or unwillingly, is the whole sense of the deed of the hero.

But the hero-soul goes boldly in—and discovers the hags converted into goddesses and the dragons into the watchdogs of the gods.

The boon brought from the transcendent deep becomes quickly rationalized into nonentity, and the need becomes great for another hero to refresh the word.

How teach again, however, what has been taught correctly and incorrectly learned a thousand thousand times, throughout the millenniums of mankind’s prudent folly? That is the hero’s ultimate difficult task.

The first problem of the returning hero is to accept as real, after an experience of the soul-satisfying vision of fulfillment, the passing joys and sorrows, banalities and noisy obscenities of life.

The story of Rip van Winkle is an example of the delicate case of the eturning hero.

In deep sleep, declare the Hindus, the self is unified and blissful; therefore deep sleepis called the cognitional state.

The equating of a single year in Paradise to one hundred of earthly existence is a motif well known to myth. The full round of one hundred signifies totality. Similarly, the three hundred and sixty degrees of the circle signify totality; accordingly the Hindu Puranas represent one year of the gods as equal to three hundred and sixty of men.

Sir James George Frazer explains in the following graphic way the fact that over the whole earth the divine personage may not touch the ground with his foot. “Apparently holiness, magical virtue, taboo, or whatever we may call that mysterious quality which is supposed to pervade sacred or tabooed persons, is conceived by the primitive philosopher as a physical substance or fluid, with which the sacred man is charged just as a Leyden jar is charged with electricity; and exactly as the electricity in the jar can be discharged by contact with a good conductor, so the holiness or magical virtue in the man can be discharged and drained away by contact with the earth, which on this theory serves as an excellent conductor for the magical fluid. Hence in order to preserve the charge from running to waste, the sacred or tabooed personage must be carefully prevented from touching the ground; in electrical language he must be insulated,

The wife is insulated, more or less, by her ring.

And the myths—for example, the myths assembled by Ovid in his great compendium, the Metamorphoses—recount again and again the shocking transformations that take place when the

insulation between a highly concentrated power center and the lower power field of the surrounding world is, without proper precautions, suddenly taken away. According to the fairy lore of the Celts and Germans, a gnome or elf caught abroad by the sunrise is turned immediately into a stick or a stone.

The returning hero, to complete his adventure, must survive the impact of the world. Rip van Winkle never knew what he had experienced; his return was a joke

The encounter and separation, for all its wildness, is typical of the sufferings of love. For when a heart insists on its destiny, resisting the general blandishment, then the agony is great; so too the danger. Forces, however, will have been set in motion beyond the reckoning of the senses. Sequences of events from the corners of the world will draw gradually together, and miracles of coincidence bring the inevitable to pass.

Not everyone has a destiny: only the hero who has plunged to touch it, and has come up again—with a ring.

5. Master of the Two Worlds

Here is the whole myth in a moment: Jesus the guide, the way, the vision, and the companion of the return. The disciples are his initiates, not themselves masters of the mystery, yet introduced to the full experience of the paradox of the two worlds in one. Peter was so frightened he babbled.28 Flesh had dissolved before their eyes to reveal the Word. They fell upon their faces, and when they arose the door again had closed.

We do not particularly care whether Rip van Winkle, Kamar al-Zaman, or Jesus Christ ever actually lived. Their stories are what concern us: and these stories are so widely distributed over the world—attached to various heroes in various lands—that the question of whether this or that local carrier of the universal theme may or may not have been a historical, living man can be of only secondary moment. The stressing of this historical element will lead to confusion; it will simply obfuscate the picture message.

What, then, is the tenor of the image of the transfiguration? That is the question we have to ask. But in order that it may be confronted on universal grounds, rather than sectarian, we had better review one further example, equally celebrated, of the archetypal event.

The disciple has been blessed with a vision transcending the scope of normal human destiny, and amounting to a glimpse of the essential nature of the cosmos. Not his personal fate, but the fate of mankind, of life as a whole, the atom and all the solar systems, has been opened to him; and this in terms befitting his human understanding, that is to say, in terms of an anthropomorphic vision: the Cosmic Man. An identical initiation might have been effected by means of the equally valid image of the Cosmic Horse, the Cosmic Eagle, the Cosmic Tree, or the Cosmic Praying-Mantis.

The Cosmic Man whom he beheld was an aristocrat, like himself, and a Hindu. Correspondingly, in Palestine the Cosmic Man appeared as a Jew, in ancient Germany as a German; among the Basuto he is a Negro, in Japan Japanese.